Inline vs Angle Tenons for Compound Mortise and Tenon Joints

While more obscure than the age old pins or tails first argument, another proverbial hornet’s nest discussion is whether to cut angled tenons or inline tenons when making angled or compound mortise and tenon joints. I’m no chair maker (the most prevalent use of these joints) but I spent the weekend cutting compound tenons while filming a Hand Tool School lesson. This was the first time I did a lot of these joints consecutively. In the past I have cut maybe two of these while making a project. While a good learning experience, it is nothing compared to making 30 of these joints in a single shop session. That pretty much sums up my weekend and my thrill-a-minute lifestyle :). So flush with this experience I have my own conclusions. I fall in the inline tenon camp.

Let me ‘splain…

The argument is that because the inline tenon with angled mortise is harder to cut, the angled tenon with square mortise is a good alternative that doesn’t greatly sacrifice strength of the joint. The opposite view is that the reduction in strength due to grain run out in the tenon is something that cannot be overlooked in a high stress joint like the back leg of a chair. Pictured are two tenons that make up joints with a 10 degree splay. The angled tenon on the right makes the deviation away from the grain while the inline tenon on the right stays parallel to the grain. Obviously the more the tenon can parallel the grain the stronger it will be so the angled tenon technically is weaker. However look at the splay on this joint which is pretty typical of the trapezoidal seats of classic chairs. It really doesn’t deviate much from the grain at all and I can’t imagine it would sacrifice much strength.

The argument is that because the inline tenon with angled mortise is harder to cut, the angled tenon with square mortise is a good alternative that doesn’t greatly sacrifice strength of the joint. The opposite view is that the reduction in strength due to grain run out in the tenon is something that cannot be overlooked in a high stress joint like the back leg of a chair. Pictured are two tenons that make up joints with a 10 degree splay. The angled tenon on the right makes the deviation away from the grain while the inline tenon on the right stays parallel to the grain. Obviously the more the tenon can parallel the grain the stronger it will be so the angled tenon technically is weaker. However look at the splay on this joint which is pretty typical of the trapezoidal seats of classic chairs. It really doesn’t deviate much from the grain at all and I can’t imagine it would sacrifice much strength.

So why not use an angled tenon since it is easier to cut?

First, laying out this joint is more difficult. Since the end of the shoulder is angled and the tenon is drawn perpendicular to that angle, a typical mortise gauge can’t be used. Instead I found laying them out with my bevel gauge referenced against the end grain to be the best method though it was not very easy and allowed for a fair amount of error to creep into the joint from one to another. This can be a problem when 2 to 4 of these need to be cut when making a seat frame.

First, laying out this joint is more difficult. Since the end of the shoulder is angled and the tenon is drawn perpendicular to that angle, a typical mortise gauge can’t be used. Instead I found laying them out with my bevel gauge referenced against the end grain to be the best method though it was not very easy and allowed for a fair amount of error to creep into the joint from one to another. This can be a problem when 2 to 4 of these need to be cut when making a seat frame.

The inline tenon however is cut just like any other tenon and the angle is introduced only in the shoulder. A mortise gauge can be set once and used to do all the tenons and mortises thereby increasing accuracy considerably.

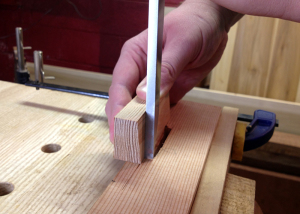

On the converse, the inline tenon requires an angled mortise. This scares a lot of people in both the hand tool and power tool camps. I submit that the joint isn’t hard to cut at all and when done by hand, no special sleds or jig (other than a scrap block) are needed. I grabbed a small black and planed in the angle of the splay then used it as a guide for my mortise chisel. One the initial pass is made with the chisel, chopping deeper is guided by the wall of the mortise already established. In the end, I found it no more difficult than chopping a square mortise.

Easier Layout, Same cutting difficulty, inline tenon is the way to go.

So with that difficulty removed and the layout being simpler, the inline tenon seems the obvious choice. Why worry about whether or not the tenon is stronger this way when cutting it isn’t any more difficult or time consuming than the angled tenon. What we know about wood says that the inline tenon should be stronger so to me why tempt fate?

I think what really drives this debate is a difference between the woodworker reliant on power tools for accuracy and the woodworker who can cut a joint with hand tools. Angles mean nothing when you use a hand saw or chisel but trying to set up your machines to cut compound angles is another matter completely. I’m decidedly bias but I find this angle tenon debate a simple one to solve when viewed from the hand tool solution. Of course it helps that many of the chair makers I respect agree with me since I’m a novice when it comes to making chairs.

Your Turn

Do you find the angled tenon to be weaker than the inline tenon? Is the inline tenon actually harder to cut? Please share your experience and insight in the comment section below.