A Book for Design Standards

Recently WoodTalk did an interview with Brandon Gore, judge from the TV design show “Framework”. There were a lot of gems in that 30 minutes but one that stuck with me the most was how without function furniture is art. Now there is nothing wrong with art, but when I’m tired after a long day at the lumber yard I don’t want to sit on my Hieronymus Bosch. So a chair should be comfortable and a dining table should be at the right height, etc, etc. But what exactly are those dimensions and how does a woodworker know other than building the piece and using it?

Recently WoodTalk did an interview with Brandon Gore, judge from the TV design show “Framework”. There were a lot of gems in that 30 minutes but one that stuck with me the most was how without function furniture is art. Now there is nothing wrong with art, but when I’m tired after a long day at the lumber yard I don’t want to sit on my Hieronymus Bosch. So a chair should be comfortable and a dining table should be at the right height, etc, etc. But what exactly are those dimensions and how does a woodworker know other than building the piece and using it?

Prototypes are great, but just knowing where to start so that initial prototype doesn’t turn into version 18 requires some knowledge of what sizes are need for good, functional design. We can’t all be Tony Stark and fabricate 30 versions of a model while we sleep.

Hidden within this interview with Brandon was a passing mention of a design standards book that he likes. I had to rewind it to catch it so you may have missed it. Brandon mentioned that his favorite book to consult in figuring out these functional dimensions is “Human Dimension & Interior Space“. I don’t know about you guys, but the episode was still playing in my ears while I was on Amazon spending $26 on this book that is more textbook than anything else. I remember what I paid for textbooks in college so this is a bargain! In typical Amazon fashion, the book show up on my doorstep 5 minutes before I added it to my shopping cart so I’ve had several days to read through it.

Encyclopedic is probably the best word for this. If you can think of a situation where humans interact with an object (or another human) this book has laid out optimal dimensions for that interaction. I’m not exaggerating here at all. If you land a job to design furniture for the waiting room of a dental office, there is a section in here for you. Don’t mix it up with the waiting room of a legal office either; mass hysteria will ensue.

Encyclopedic is probably the best word for this. If you can think of a situation where humans interact with an object (or another human) this book has laid out optimal dimensions for that interaction. I’m not exaggerating here at all. If you land a job to design furniture for the waiting room of a dental office, there is a section in here for you. Don’t mix it up with the waiting room of a legal office either; mass hysteria will ensue.

Moreover it backs this data up with anatomical and social studies explaining why that table should be X high or the foyer in your house should be X feet wide. The chapter on bathrooms explains a lot about why my house is so hectic in the morning when my wife and I are both trying to get out the door and bumping into each other. Apparently the architect who built my house in the 1960s didn’t read this book. (probably because it was first published in 1979).

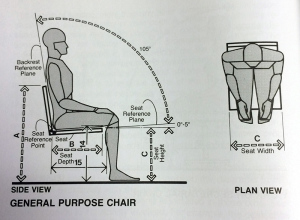

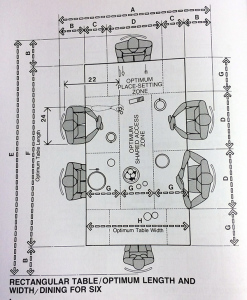

The average humble furniture maker is bound to be overwhelmed by the sheer volume of raw data and charts in this book but I highly recommend digging into it. The chapters on chairs alone are well worth the asking price. There is intense detail about how slight changes in height or angle add pressure in certain areas of the body. The chapter on tables as well clearly lays out the elbow room needed as well as typical spacing across the table not only for ergonomic reasons (reaching the salt) but also for social reasons. The segment on “comfort spaces” based upon relationship to one another is really interesting and makes you think not only about whether the table is functional but is it functional based upon who is using it.

The average humble furniture maker is bound to be overwhelmed by the sheer volume of raw data and charts in this book but I highly recommend digging into it. The chapters on chairs alone are well worth the asking price. There is intense detail about how slight changes in height or angle add pressure in certain areas of the body. The chapter on tables as well clearly lays out the elbow room needed as well as typical spacing across the table not only for ergonomic reasons (reaching the salt) but also for social reasons. The segment on “comfort spaces” based upon relationship to one another is really interesting and makes you think not only about whether the table is functional but is it functional based upon who is using it.

Truthfully this is a book that should sit on any woodworker’s shelf. It is not a reading book, but a reference book. Though I must admit the opening chapters on Anthropometric Theory touched a nerve with me and took me back to the report I wrote on Ergonomic Engineering back in high school when I was able to meet and interview a NASA engineer who helped to design living spaces on the space station.

You start to realize there is more than just inches going on here. Good, functional design can exist on dimensions alone,

but great design has heart that examines the connection between comfort and human relationships and provides a solution.